Introduction

“A slut is a person of any gender who has the courage to lead life according to the radical proposition that sex is nice and pleasure is good for you,” write Dossie Easton and Janet Hardy in The Ethical Slut: A guide to infinite sexual possibilities.

In doing so, they create space for every sexual possibility except for one: the possibility to consider whether sex may not be nice.

Some might suggest this space exists, already populated by woman-haters, given the shame, hatred and violence on offer for women who dare to have sex on their own terms. But these moralistic right-wing views don’t hold that sex is not nice – they hold that women who have sex (and others who are seen to be treated as women in sex) are not nice.

As such it is both progressive and radical to say that sex is not shameful for women, and that a woman should not be punished for her sexual choices; radical, because shaming and punishment are both commonplace.

But in the present day it is not radical to say that “sex is nice”. If anything, it’s tautological. Sex, for all practical purposes, is defined much of the time as only “that which is nice” – in many feminist discourses, if it is not nice, it is not sex.

This precludes certain ways of thinking about sex. I would like to look at the things we are able to think when we allow ourselves to criticise not just singular sex acts but the ‘niceness’ of sex under patriarchy as a whole.

We will describe sex-negativity as a worldview or mode of analysis, not a belief system or a system of morals. The goal is not to determine that ‘sex is bad’ – though the analysis does not preclude this conclusion – but to use this way of thinking to better understand sex and sexuality under patriarchy.

Trigger and Content Warnings

Trigger Warnings: This article discusses the intersections of sex, violence and power. It discusses rape and, tangentially, prostitution and pornography. It reproduces (in order to criticise) date-rape apologism. It uses the word ‘fuck’ a lot, in the carnal sense. There is one graphic description of the sex/violence/power overlap which is warned for in the text and preceded by a link to skip it.

Content Warnings: This article talks about the violence and power relations inherent in heterosexuality and in intercourse. It touches on the ways in which under male supremacy the receptive partner in intercourse is considered to be demeaned. It describes compulsion into heterosexuality and into sexual power relations reflecting heterosexuality.

Contents

- Introduction

- Trigger and Content Warnings

- A Note On Intersectionality

- Why Reclaim ‘Sex-Negative’?

- Tenets of a Sex-Negative Feminist View of Sex:

- What Is Not Sex-Negative Feminism

- Sex-Negative and Sex-Positive Feminisms and Popular Woman-Hating

- The Ethical Prude

- Conclusion

A Note On Intersectionality

Throughout this article, sexuality will be discussed in terms of how it is structured by patriarchy and heterosexual normativity. Since patriarchy and heteronormativity are dominant orders, by definition they have significant power to determine what it is that sex means.

From reading, and from conversations with friends, I feel sure that racist and imperialist systems such as colonialism and historical and present-day slavery also have the power to structure sexuality. I don’t feel able to write meaningfully on these subjects, or even widely-read enough to signpost the reader to the relevant arguments. So I acknowledge that this article will be deficient twice-over in the way it addresses power, violence and compulsion within sexuality.

First, because in omitting the ways in which the above systems influence sexuality, this becomes effectively a piece on white sexuality. Second, because it is not even that: white sexuality does not exist outside of colonialism, in that the white woman is in fact the colonial woman, the white man’s power built on stolen lives and stolen land.

Against these significant omissions, I hold the risk of attempting to cram an analysis of colonialism into the structures of feminism I practice today, in misrepresenting and framing the arguments of non-white feminist, womanist and other progressive women, in erasing one voice through platforming another. I acknowledge that this is not an inescapable dilemma and that the solution is for me and other white feminists to learn more on these subjects, something we must do consciously or it will never happen.

For now, I feel the right thing to do is to admit the significant gap in my analysis and to continue to read and grow as a feminist before I can learn whether it is useful for me to write on these subjects. In the meantime, I will eagerly include links to any articles readers may suggest which compliment this article from a postcolonial perspective, or address ways in which the white-centric, gender-centric approach I have taken here may erase other dynamics. I would be especially grateful for suggestions of books or theories it could be useful for me to study.

I shall primarily use “woman” in place of “white woman” through the remainder of this piece (likewise “man”), because I don’t think that none of these issues affect non-white women. But I would ask the reader to remember the disclaimers above and to not read this as a total theory of the experience of all women. It is one part of the puzzle, no more.

Finally, as a lesbian woman, I feel as if I need to justify my focus on hetero sexualities. I do this because I am painfully aware that heterosexuality influences the mainstream more than lesbianism. In discussing the sexual norms of society primarily in terms of the sexual oppression of women by men, this article does not mean to suggest that other sexualities and sexual dynamics do not exist or do not matter – it means that they do not matter to the mainstream, that they do not have the same power to change the way in which society thinks about sex.

Why Reclaim ‘Sex-Negative’?

When many feminists call an act ‘sex’, they are often careful to distinguish it from other acts which may appear superficially similar, acts during which one partner violates another’s boundaries. They call the latter ‘rape’ instead of ‘sex’ and treat the two categories as mutually exclusive. In doing so they rely on an analysis of rape which understands it as an act of violence, power and hostility. By implication, sex is none of those things.

This analysis places them in a minority. In a rape culture, rape is also called sex, even though it is not nice. Sex acts under coercion are called sex. Sex within marriage is called sex. Pornography does not depict (at best) a kind of genre theatre of power and vulnerability centred on the image of the woman-as-whore, it it said to depict sex, even though the actors are likely to find the paycheck (if there is a paycheck) much nicer than the sex. Sex over unnegotiatable power gradients and sex over severe power gradients in which no effort is made to offset power – it’s all called sex.

Feminists do not own the word ‘sex’. It will not mean what we define it to mean. It will, pending the overthrow of patriarchy, continue to mean what it has always meant.

This particular feminist separation of sex and power/violence is beneficial in that it allows feminists to conceive of the kind of sex we would like ourselves and others to have the opportunity to have. The cost of thinking in that way is that we can forget how, out in the real world, rape, power and sex are experienced at best on a continuum and at worst helplessly intermingled.

If we do not use our own special language, in which sex is what is nice, and everything else is not sex, it should be plain that we must at least consider the possibility that sex, as it is typically experienced, is often not nice.

What other recreational activity is defined like this? It’s neither radical nor prosaic to say that rock-climbing is intrinsically nice; it’s just a bit odd. You can love it, I can hate it, but that does not give it an objective value. Someone who doesn’t like it is not wrong or bad, they’re simply not invited rock-climbing.

But there are words for people who criticise sex. If an individual states or implies that they do not like sex for themselves (whether they are asexual and/or whether they have personal reasons to criticise sex) they are called a prude. They may also be called frigid or damaged or be accused of being gay (when turning down sex from people of a different gender) or straight (when turning down sex from people of a similar gender). But it is when an individual articulates a political criticism of sex that the heavy guns are wheeled in. The name used for this kind of person and their politics is sex-negative.

Who would be sex-negative? It’s like being anti-choice, or pro-death. It’s practically being anti-nice! The words are meant to stop us in our tracks, and to some extent they have. But I would like to brave those words to look at what we might mean by an authentic sex-negative feminism (hereafter: sex-negative feminism).

Not the opposite of sex-positive feminism, and not the woman-policing of the right. A feminism which articulates a radical critique of sex and which dares to consider the proposal that sex may not, inherently, be nice. And perhaps, in much the same way as Easton & Hardy set their sights on ‘slut’, we might reclaim that bad word ‘prude’ while we’re at it.

Tenets of a Sex-Negative Feminist View of Sex

A sex-negative feminist observes:

- That society is male-supremacist and that male supremacy extends into every aspect of experience, including sex

- That, under patriarchy, sexuality is invested with qualities of power and/or violence, as exercised by men, or male proxies, upon women, or female proxies

- That, under patriarchy, power and violence – and apparent vulnerabilities to power and violence – are in turn typically invested with sexual qualities

- That, under patriarchy, men are considered to have a right of sexual (and otherwise) access to women, a right which it is compulsory for women to grant and for men to exercise, the burden of meeting this compulsion falling unequally on women

- That a sex-negative feminist must stand against these issues and may be proud to be called a prude, if she does not shame other women

The remainder of this article will discuss each of these tenets in turn and end by contextualising sex-negative feminism alongside other views of sexuality, as well as clarifying some of the bad press which sex-negativity as a mode of analysis and a politics has received.

Male Supremacy Structures Sexuality

Radical feminists believe that male supremacy – a belief in and a condition of the supremacy of men over women, codified in part as ‘gender’ – is and always has been fundamental to the society in which we live. As such, it should be no surprise that societally approved sexualities are male-supremacist.

In Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law, MacKinnon defines a relation between gender and sexuality as follows:

Stopped as an attribute of a person, sex inequality takes the form of gender; moving as a relation between people, it takes the form of sexuality. Gender emerges as the congealed form of the sexualization of inequality between men and women.

For this essay, the key phrase is ‘sexualization of inequality’: the cultural value which holds that the unequal power dynamics between women and men are hot. In case this sounds satirical, let me be clear: I believe that most if not all of us are to some extent trapped within this dynamic. I know that I am.

Sex Is Power

In her famous work, Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, Susan Brownmiller made the critical observation that rape is an act of power. She used this observation to draw a line between sex and rape, one widely referenced in feminist discourse, most simply summed up in her assertion that:

… rape is a deliberate distortion of the primal act of sexual intercourse – male joining with female in mutual consent…

– Brownmiller, Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (Ballantine Books, 1993), p369

Note the description of intercourse as definitively consensual. Intercourse is consensual and nice. Rape is not. This can be seen earlier in the book where Brownmiller first quotes the Freudian psychiatrist, Dr. Guttmacher:

Apparently, sexually well-adjusted youths have in one night… committed rape…

Ibid., p178

Brownmiller continues:

[Guttmacher’s] chilling passing observation that rapists might be sexually well-adjusted youths was a reflection of his Freudian belief in the supreme Rightness of male dominance and aggression, a common theme that runs through Freudian-oriented criminological literature. But quickly putting the “sexually well-adjusted youths” aside…

Ibid., p178

As sex-negative feminists, we may wish to dispute Brownmiller’s analysis and the ease with which she sets aside Guttmacher’s assessment.

Not because we disagree with her that rape is an act of power. What we may dispute is the assumption that sex is not an act of power. Nobody could consider rapists to be “sexually well-adjusted”, per se. But we may ask: well-adjusted to what? If we consider whether Guttmacher’s “youths” might be better described as sexually normatively-adjusted, we find ourselves in agreement with neither the latter-day Freudians or with Brownmiller. The normal culture they are adjusted to is, of course, rape culture.

A great amount of sex takes place over the power relation of sexism, existing not only between men and women as classes but between individual men and individual women as power-over; we can observe that in most cases, that power relation goes unacknowledged. Unchallenged, it is not separate to the sex act, it is integral to it.

MacKinnon makes this point in Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State, where she writes that:

The point of defining rape as “violence not sex” or “violence against women” has been to separate sexuality from gender in order to affirm sex (heterosexuality) while rejecting violence (rape). The problem remains what it has always been: telling the difference. The convergence of sexuality with violence, long used at law to deny the reality of women’s violation, is recognized by rape survivors, with a difference: where the legal system has seen the intercourse in rape, victims see the rape in intercourse. The uncoerced context for sexual expression becomes as elusive as the physical acts come to feel indistinguishable. Instead of asking, what is the violation of rape, what if we ask, what is the nonviolation of intercourse? To tell what is wrong with rape, explain what is right about sex. If this, in turn, is difficult, the difficulty is as instructive as the difficulty men have in telling the difference when women see one. perhaps the wrong of rape has proven so difficult to articulate because the unquestionable starting point has been that rape is definable as distinct from intercourse, when for women it is difficult to distinguish them under conditions of male dominance.

I thoroughly recommend reading the entire piece, which makes this and several other points far more clearly than I ever could. While doing so, note that analysis such as MacKinnon’s is impossible without discarding or suspending the predicate of ‘sex is nice’ – as MacKinnon does – to consider the alternatives.

“Sex is nice and pleasure is good for you” is a powerful motto for those for whom sex has been nice, or for those who would like to experience it as nice. It is less encouraging to those who have experienced sex as violating and/or unwanted; simply telling them that what they experienced was not sex, or the offer of sex, is small comfort when it appears indistinguishable from what the rest of the world calls sex, and when the rest of the world insists that it was sex.

Catharine MacKinnon also addressed this subject in Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law:

Men who are in prison for rape think it’s the [most stupid] thing that ever happened… It isn’t just a miscarriage of justice; they were put in jail for something very little different from what most men do most of the time and call it sex. The only difference is they got caught. That view is nonremorseful and not rehabilitative. It may also be true.

We need to be able to admit that what perpetrators do is what the world calls sex, and that it is not nice, and that it is not the fault of survivors and its other casualties for not finding it nice but is in fact due to the nature of sex under patriarchy.

Sex-negative feminist analysis holds this nature in the foreground and uses it to ask, “What does this allow us to understand?”

As an example, we can apply this kind of analysis to the case of date rape, or so-called “grey rape” (as described in Lisa Jervis’ article, An old enemy in a new outfit: How date rape became gray rape… and why it matters, published in the anthology Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape; the article is discussed in this interview).

When Whoopi Goldberg suggested that the actions of rapist paedophile Roman Polanski were not really “rape-rape”, there was a feminist outcry. Rightly, feminists made the point that there is not a class of rape which is ‘rape lite’. And yet Goldberg is expressing a mainstream viewpoint. Many feminists recognise that part of the problem is that rape is not taken seriously. But it takes sex-negative feminism to understand precisely how date rape apologism actually functions.

To the date-rape apologist, it is not “rape-rape” because the script for date rape is close to the script for sex, and because sex is nice (or at least socially sanctioned). If sex is nice, then a script for sex cannot be a script of power. If a script for sex is not about power, then a script for date rape is not about power. If date rape is not about power then it is not, cannot be “rape-rape”: not like violent stranger rape, real rape.

The entire argument is predicated on “sex is nice”, but we dispute this premise. The sexual scripts followed by people of all ages are scripts of power. Power and violence are not even just qualities of sex acts in the same way as sexual positions, forms of touch and the romantic/erotic connection are qualities of sex acts. They also precede and follow the act, coercing participation and silencing women who only understand a sex act as rape after the event, as touched on in Under Duress: Agency, Power and Consent, Part One: “No”.

So it shouldn’t be a surprise that sometimes those scripts lead to something nice, and that sometimes they enable rape. If anything, it should be a surprise that they lead to sex which is nice as often as they do. Insofar as scripts of power are experienced as ‘nice’, that offers us an important clue to the extent to which power, violence and coercion are experienced directly as erotic; the subject of the next section.

Power is Sexy

If qualities of power and violence are integral to sex, as argued above, we can also observe that qualities of ‘sexiness’ are integral to many depictions and experiences of power and violence. That is to say, power and violence are culturally invested with sexual qualities; they are eroticised. As MacKinnon puts it, again in Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State:

Rape is not less sexual for being violent; to the extent that coercion has become integral to male sexuality, rape may be sexual to the degree that, and because, it is violent.

In Zack Snyder’s film, Sucker Punch (I won’t apologise for the spoilers, it’s a terrible film), the female protagonist is institutionalised and retreats into a fantasy scenario in which she is prostituted along with a number of other women. Each time she is offered to a john, the film depicts her as dancing for him (‘dancing’ – there’s a euphemism) before it cuts away to a second layer of fantasy in which, dressed in a variety of fetish outfits, she participates in a series of sequences of stylised videogame-esque violence. Why violence? Because violence satisfies the sexual urge of the male viewer. It is not analogous to the sex act; it is the sex act.

(Potential Trigger Warning: The next paragraph is graphic and intended for readers who find it difficult to accept the argument that power and violence are eroticised. Readers who have no problem accepting this and would rather not read about it in detail may wish to skip to the next paragraph.)

Violent women are sexy, violence is sexy, women are sexy, sex is violence, violence is death is sex. In part this is because the scene is a scene of women, and all actions taken by women are symbolic stand-ins for sex, whether they are shooting Nazis or jogging down the street wearing sweats. The twist: because violence is traditionally done to women (coded as a sex act) the male viewer who knows this (all male viewers) can fantasise about a world in which he is not guilty, because he does not have the monopoly on violence – all the while enjoying the sexualised violence she performs, her long legs kicking, her clothes tight, blood on her body. Violence is adrenaline, dizzying fast motion, pain and women in danger; a pornography of the body in extremis, ending in deaths, la petite mort or otherwise. After the violence/sex act, the protagonist is sweating; exhilarated; and the john is satisfied: money well spent – a sentiment not shared by the critics, who prefer to have it known in public that they prefer a little more plot with their rape.

Before we leave the subject of Sucker Punch, I may as well share this analysis of the film by TumblinFeminist (trigger warning for the link, for all the above plus the treatment of women in institutions):

I think this is a rather acurate representation of what many survivors of sexual abuse and dissasociative dissorders go through, myself included.

If it is, it is by accident, or via the stumbling-on of a hidden truth. Snyder is no crypto-feminist; the gaze in Sucker Punch is the rapist’s gaze, not the survivor’s gaze. If the film is a film about the process of survival, then it is dissassociation performed as pornography, a second-order thrill for those who eroticise not just violence but the act of surviving violence itself.

Moving on, this kind of sleight-of-hand in which power and violence are substituted for sex can also be found in sexual media produced for women.

Most UK and perhaps some other readers will be familiar with Mills and Boon novels. For those who are not, as well as those who do not make the connection between power and sex in Mills and Boon’s Harlqeuin ‘romances’ (and those scare quotes! as if there is a true kind of romance which does not eroticise power, a ‘nice’ romance unbracketed by quote marks and taking place outside of patriarchy), I offer the writing guidelines from their own website, covering two genres, ‘Harlequin Presents’ and ‘Harlequin Desire’:

When the [Presents] hero strides into the story he’s a powerful, ruthless man who knows exactly what – and who – he wants and he isn’t used to taking no for an answer! Yet he has depth and integrity, and he will do anything to make the heroine his.

The Desire hero should be powerful and wealthy – an alpha male with a sense of entitlement, and sometimes arrogance. While he may be harsh or direct, he is never physically cruel.

The men are not sexy solely because they are physically attractive, or because they appear to be good lovers; or rather, they are sexy to the extent that they demonstrate the characteristics associated with male lovers under patriarchy, namely that they are confident in wielding power. And the sex in these books does not begin with “passionate lovemaking” (quote sourced from the guidelines); each time the male romantic exercises power, that exercise of power does not just contribute to the reader’s “blistering sexual anticipation”; it is experienced directly as sex by the female protagonist. As she experiences male power, she trembles, she flushes, she falls in love; her world is penetrated and violated by the male presence.

The perfect romance

The romance genre also offers us a clear understanding of the woman’s role in such a story. Again, from the ‘Presents’ and ‘Desire’ genres:

Though she may be shy and vulnerable, [the Presents heroine] is also plucky and determined to challenge his arrogant pursuit.

The Desire heroine is complex and flawed. She is strong-willed and smart, though capable of making mistakes when it comes to matters of the heart…

The woman must be available to the exercise of male power: “vulnerable” for the Presents heroine, “flawed… and capable of making mistakes” for the Desire heroine. But she must also be worthwhile: “plucky and determined”, “strong-willed and smart”.

Unlike the heroes, though, the women’s strength is not directed towards living their own lives:

Beneath his alpha exterior, [the Desire hero] displays some vulnerability, and he is capable of being saved. It’s up to the heroine to get him there.

Her goal is to save the man, and the Presents heroine above is described as ‘determined to challenge his arrogant pursuit’, that is, to resist the man. Needless to say, the Desire heroine succeeds, the Presents heroine fails, but both of them direct their “plucky” energy entirely towards the hero.

(Do we need to discuss his so-called “vulnerability”? These novels do not depict male vulnerability. They depict a woman-sized gap in a man’s broad-spectrum exercise of power on the world around him, a place which she can occupy to take the force of his power upon herself rather than have it used on others. She is not just expected to take this place and to try to ‘save’ him and those around him; she actively longs to. What else is a woman for?)

What is ‘sexy’ in romance novels is male power and independence, operating against the vulnerability of a woman whose world is centred on that male power. This is the dynamic of heterosexuality under patriarchy, a dynamic in which we are indoctrinated from birth as compulsory, and one from which non-hetero-sexualities must differentiate themselves or be subsumed. The compulsory nature of hetero- and other sexualities is the subject of the next section.

Sex Is Compulsory

In preparing this section, like any good essayist, I searched for definitions of compulsory sexuality using Google. The results were disappointing, so I’ve prepared my own definition:

‘Compulsory sexuality’ refers to a set of social attitudes, institutions and practices which hold and enforce the belief that everyone should have or want to have frequent sex (of a socially approved kind).

Compulsory sexuality differs from sexuality in that it is imposed from without, whereas sexuality is discovered from within. Compulsory sexuality states: “You must have sex, you must want sex”, but sexuality arises from a dynamic between people in which they reach a mutual recognition that, “We would like to have sex”.

The two are not entirely separable as compulsion becomes internalised. Thus, our sexualities are twisted into knots such as, “I want to want sex”, or, “I want to want the sex I am having”; conformity to the compulsion becomes the normative sexuality, deviation from it is experienced as pressure from within as well as without.

As this section covers a number of different expressions of compulsory sexuality, I’ve split it into sections on heterosexual, queer, asexual and “unfuckable” people, ending with a section on the way in which value is assigned to people based on the extent of their visible participation in sexuality.

Compulsory Sexuality For Heterosexuals

As a dominant sexual order, patriarchy ensures that the above definition is not neutral with regard to gender. Compulsory sexuality is strongly linked with compulsory heterosexuality, defined by Adrienne Rich in her definitive piece on the subject, Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence, as an ideology which preserves:

Male right of physical, economical, and emotional access [to women].

I retain Rich’s term ‘compulsory heterosexuality’ despite the fact that women of many sexual orientations have sex with men, and that men of many sexual orientations have sex with women, and that people of other sexes and other sexual orientations also have sex with men, women and people of other sexes. I do so because patriarchy will sanction the sexual behaviours of those people to the degree to which it considers their sexual practice to resemble heterosexuality, and punish them to the extent that it considers them to diverge.

Put more simply, this all means: in the eyes of patriarchy, “men gotta fuck women”. If you are a woman not being fucked by a man, you are doing ‘woman’ wrong, and if you are a man who is not fucking women, you are doing ‘man’ wrong. (The consequences of doing ‘woman’ wrong are, of course, significantly more punitive than doing ‘man’ wrong, because women are always closer to consequences under patriarchy.)

In mainstream culture, “gotta fuck” is channelled into morally constrained paths. Thus it is “gotta fuck in marriage”; except we all know that the “in marriage” clause applies more to some than others. Andrea Dworkin describes in detail the ways in which systems of laws and morals are used to best preserve male right of sexual access in several of her books (all an essential read for the budding sex-negative feminist); this quote is from Right Wing Women:

All of the sexual prohibitions in Leviticus, including the prohibition against male homosexuality, are rules for effectively upholding the dominance of a real patriarch, the senior father in a tribe of fathers and sons. The controlling of male sexuality in the interests of male dominance – whom men can fuck, when, and how – is the essential in tribal societies in which authority is exclusively male… The heinous crime is in committing a sexual act that will exacerbate male sexual conflict and provoke permanently damaging sexual antagonism in the tribe among men.

Among other things, the ‘sexual antagonism’ Dworkin refers to is the disruption of male sex-right and the possible subjection of men to male sex-right.

Compulsory Sexuality For Lesbian, Bisexual and Gay People

The Dworkin quote above also suggests that compulsory heterosexuality might be incompatible with non-heterosexual communities. Unfortunately, that is not the case. Patriarchy is flexible, adapting to fit its circumstances, and many non-heterosexual spaces have taken this “gotta fuck” mandate and created their own versions.

Those revisions could be described in non-hetero, homo/bi-normative terms such as “men gotta fuck men”, “women gotta fuck women”, “people gotta fuck people”, etc. But patriarchy can’t be prised from our minds or bedrooms that easily. It’s MacKinnon again, this time in Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, who supplies us with a pithy definition of the male-supremacist meaning of ‘fuck’:

Man fucks woman; subject verb object.

Male-supremacist heterosexuality is more than just the man-woman relationship – at its most basic, it is the subject-object relationship. To understand how compulsory heterosexuality affects non-heterosexual spaces, we must ask who are the subjects of the fuck and who are the objects of the fuck? Are the subjects masculine or assertive or enthusiastic or popular or experienced or on top or otherwise privileged? Are the objects feminine or passive or reluctant or unpopular or new to the scene or on the bottom or otherwise marginalised?

There is a reason why heterosexual people are obsessed with asking similar-sex couples, “So, who’s the man?” They want to know who fucks and who, as it were, is fucked. Because sex is power – specifically, the exercise of male power upon women – then any time power is exercised, it invokes the spectre of male and female roles. When sex is defined by power, determine who has the power in the fuck and who does not, or who gains social status in the fuck and who loses it, and you will discover who must compulsorily be fucked by whom.

This is one way in which heterosexuality can be said to be ‘compulsory’ even to non-heterosexual people. Another is the way in which non-heterosexual sexualities may be coopted into the service of male right of sexual access, as described by Kathy Miriam in Toward a Phenomenology of Sex-Right: Reviving Radical Feminist Theory of Compulsory Heterosexuality:

… it’s important to note the extent to which lesbianism itself has been refigured by heteronormativity today as central to the heterosexual norm, that is, for the pleasure of men… there is a great likelihood that today, the sexual agency of lesbianism, rather than simply foreclosed by heteronormativity, is refigured in terms of men’s access to women.

(Miriam goes on to give several examples of this, which can be found in her article, but are not the main point of this piece.)

The impact of compulsory heterosexuality on bisexual people was covered in a special issue of the Journal of Bisexuality on “Bisexuality and Queer Theory: Intersections, Diversions, and Connections”, in the article, “Compulsory Bisexuality?: The Challenges of Modern Sexual Fluidity”, in which researcher Breanne Fahs found that:

Women frequently reported that they felt pressure to accommodate their male partner’s sexual fantasies that they engage sexually with other women; further, all of the young women reported that they were aware of, and had witnessed, some form of performative bisexuality either on television or in person. Pressure to perform as bisexual appeared for heterosexual-identified women and for bisexual and lesbian-identified women, though heterosexual women reported more pressure from their sexual partners whereas bisexual and lesbian women reported feeling pressure from men who were strangers and/or nonpartners.

…

Compulsory heterosexuality, however challenged by increasing acceptance of, and performance of, bisexual behavior, is still alive and well. This fact is notable in women’s descriptions of minimizing the significance of their same-sex feelings, attractions, behaviors, and experiences, and it exists when describing the ways in which same-sex eroticism often requires the literal and figurative presence of men in the sexual exchange. Women may engage in same-sex sexual behavior, but this often occurs in the presence of men, with men’s approval, and for men’s sexual arousal. Women are classically heterosexual even while performing as bisexual.

For all queers and other non-heterosexual people, I believe that compulsory heterosexuality is not just a displacement of sexual activity towards heterosexual expression. It is a coupling of sexuality with the “gotta fuck” power structures of heterosexuality which then enables power to be exerted according to those structures, compelling more sexuality than if the coupling did not exist. Queer people are cool if they are “getting some” or “putting out”, and the ‘coolness’ of those two positions derives from the value assigned to men and women participating ‘correctly’ in compulsory heterosexuality.

Compulsory Sexuality for Asexuals

As I understand it, there is an ongoing debate in asexual communities about whether compulsory sexuality and its message of “gotta fuck” is a cultural force which structurally oppresses asexual people. Most seem to agree that if it does, it does not do so exclusively or in a unique way. The subject is discussed in issue #18 of AVENues, a bimonthly newsletter/magazine featuring submissions from the asexual community. In the lead article, ‘The (A)Sexually Oppressed?’, MANDREWLITER writes that:

Being able to portray asexuals as oppressed appeals to people’s moral feelings and can be useful in making allies and doing visibility… Clearly, there is a real need to increase visibility and understanding of asexuality, but if we view ourselves as oppressed – and especially if we view ourselves as victims – there is the danger of the sense of the “unassailable moral superiority” that comes from such a self-perception.

Despite it seeming to be representative of prevailing published views on asexuality, I am a little uncomfortable including this quote as, in my opinion, reducing concepts of oppression to a “victimhood” model can be a mistake. Many of the above arguments have been made about feminism, a movement which clearly has a place and which clearly fights a structural oppression. As a relatively new movement, it may be that there has not yet been time for a sufficient diversity of asexual activists to find their voices, or it may be that there are simply no systems in which asexuals are oppressed qua (as) asexuals.

EDIT: On the subject of that ‘diversity of activists’, Framboise commented with a different analysis (click to jump to the comment):

Women [in the asexual community] nearly universally perceive structural oppression, nearly every asexual woman I know has received some form of sexual harassment and violence up to and including corrective rape upon disclosing their asexuality or just a disinterest in sex. Coercion towards sexuality for women seems to come not only from the wider culture, but from within the asexual community.

Regardless of the oppression issue, it seems clear that compulsory sexuality in its capacity as assumed universal sexuality (that everyone must be sexual) marginalises and erases asexual identities. If everyone is sexual then asexual people do not exist, or have simply not yet found the right context in which to be sexual. And in its efforts to ensure that all women are objects of the male fuck, compulsory sexuality would act against asexual women qua women, except that for asexual women there are even fewer desirable outcomes to an unwanted proposition.

Compulsory Sexuality and The Unfuckable

Some people are apparently non-consensually placed outside of “gotta fuck”. This includes some trans* women, fat women and racialised women (three groups all of which are also sometimes stereotyped as hypersexual, another way of denying that we are capable of being discriminating sexual actors as well as something used to explain away others’ rape of us), some disabled people, some older people (‘older’ typically used in a relative sense, i.e. seemingly sufficiently older than the person or group which is making the determination of age) and others (this is also touched on in my article, Significant Othering).

But this is in appearance only. To be outside of “gotta fuck” is not to be free of it. Firstly, people in all of the above groups are still targetted for rape and other forms of sexual violence, sometimes moreso via the horrific suggestion that they should be grateful that somebody deigned to fuck the unfuckable. Secondly, those perceived as unfuckable, or incapable of fucking, are lesser in a world where the distorted object-value of human beings is partially predicated on fuckability or the amount of fucking performed. This is a very specific definition of ‘lesser’, of course: when sexual attention consists of the exercise of male power and violence, for people of any sex to be sexually lesser in the eyes of men may be no bad thing.

(And if you’d like to read about the intersection between fat positivity politics and compulsory sexuality, there’s an article at Fat Body Politics discussing the subject.)

Compulsory Sexuality And Object-Value

This leads to our last definition of compulsory heterosexuality: whether you are seen as one who fucks, one who is fucked, or whether the way you are perceived is fluid based on the spaces you are in and the ways you present, your value is perceived as higher if you participate in the system of “gotta fuck” than if you do not – shaming, hatred and punishment notwithstanding.

A man who has too much sex is a horndog. But a man who has too little sex is a virgin who lives in his mother’s basement, explicitly still a child, failing to perform manhood. A woman who has too much sex is a slut. A woman who has too little… it can go two ways. She can take the route of deferred sex, saving up her sex for the ‘right’ man, all of which is still really sex, it is just considered elaborate foreplay. The practice is acceptable insofar as it eventually leads to sex. But women who truly remove themselves from or deprioritise the possibility of sexual relationships are monstrous, dried-up, man-hating, a threat to civilisation itself.

Of course, patriarchy hates all women, including sluts. But who would it prefer if it had to choose?

Is all compulsory sexuality derived from compulsory heterosexuality? Or are there other compulsions towards sexuality which operate in hetero/non-hetero spaces? I actually don’t know. But I know that if compulsory heterosexuality was eliminated or reduced, the question would become much easier to answer.

To sum up: wherever you go, whatever your sex and sexuality, compulsory sexuality is always in the room. It can be queered, channelled, refused or denied but it is present. Compulsory sexuality is sex without the joy. It is doing something that you’d love (if you love it at all) but with the boss standing behind your shoulder, criticising or praising you according to standards you do not create. It means upholding those standards if you fuck the way he says, and dealing with his censure if you fuck differently or not at all.

What Is Not Sex-Negative Feminism

As with any reclaimed term, others have reached this ground ahead of us. We can’t fully detail what sex-negative feminism is without addressing a few misconceptions as to what it is not:

Sex-negative feminism is not a repudiation or even a rebranding of historical and present-day radical feminism. It is, to all effect, that same radical feminism – I am simply interested in whether we can take back the label of “sex-negative” by clearly setting out what it stands for.

Sex-negative feminism is not the political activity of Right-Wing Women, described by Dworkin in the following quote from the book:

From father’s house to husband’s house to a grave that still might not be her own, a woman acquiesces to male authority in order to gain some protection from male violence. She conforms, in order to be as safe as she can be.

This strategy requires each woman to submit not only to her husband/warden, but to wide-ranging and restrictive moral rules for women, enforced on women by both men and other women. Women who do not meet this code are ‘ruined’ and are understood to have brought any consequences on themselves. If they had followed the code, then – according to the view of right-wing women – they would be men’s wives, in an arrangement of marriage sanctioned by the State: as safe as women may be.

Which brings us to our second ‘not’: sex-negative feminism is not moralism. If there is a critique to be made of sex – which I believe there is – then feminists must make it on political, not moral grounds. Sex is not wrong, or nasty, or shameful, or dirty. Sexual desires are not immoral. The eroticisation (as found in sexual cultures such as BDSM and much of heterosexuality) of systems of domination and submission is not morally wrong (although this should not stop us from identifying and criticising where appropriate the political characteristics of public celebration and perpetuation of eroticised views of those systems).

An exemplar of criticism that is not moral but political is the Antipornography Civil Rights Ordinance drafted by Dworkin and MacKinnon to allow anyone injured by pornography to fight back by filing a civil lawsuit against pornographers. Dworkin and MacKinnon differentiate clearly between moral and political opposition in the explanatory book, Pornography and Civil Rights: A New Day For Women’s Equality (the following quote is from the subsection named, ‘Pornography and Civil Rights’):

Law has traditionally considered pornography to be a question of private virtue and public morality, not personal injury and collective abuse. The law on pornography has been the law of morals regulation, not the law of public safety, personal security, or civil equality. When pornography is debated, in or out of court, the issue has been whether government should be in the business of making sure only nice things are said and seen about sex, not whether government should remedy the exploitation of the powerless for the profit and enjoyment of the powerful. (emphasis mine)

Whatever you may think of the approach (personally, I am in full support) you must distinguish it from the view that “pornography is dirty”. As Dworkin and MacKinnon address the issue, it is the injury and abuse of women that are “dirty” (this is, perhaps, an understatement); pornography and the industry around pornography are understood to enable (or embody) this injury and abuse; and they must be fought on those grounds.

Sex-negative feminism is not the opposite of sex-positive feminism. While it’s true that many present-day sex-positive ideas were formed in response to the second-wave critiques of intercourse and pornography, the fundamentals of sex-negative feminism are not a reaction against that reaction. While some sex-negative feminists may fail to distinguish between right-wing anti-sex moralism and our political criticism of sex, we do not need to oppose them simply because they are mistakenly opposed to us. Women are not our targets.

The sex-negative/sex-positive divide will be examined further in the next section.

Sex-Negative and Sex-Positive Feminisms and Popular Woman-Hating

Having described sex-negative feminism in detail, I would like to contextualise it alongside other feminisms and other cultural forces.

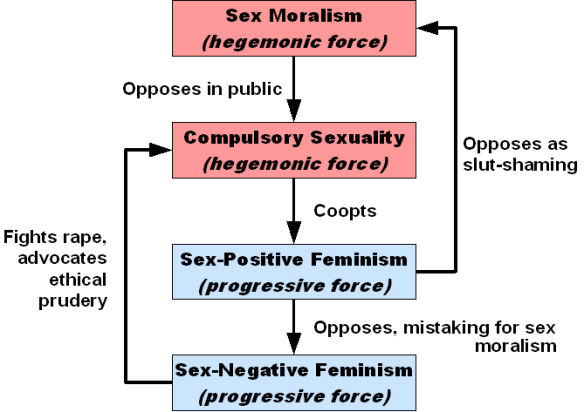

While thinking about this subject, I’ve found it useful to think of there being four primary forces which interact in primarily-White Western discourses around sexuality. I’m going to borrow a little bit of postcolonial theory at this point and say that this is not intended to be used as a map. Maps are for those with a god’s eye view, those who believe that their limited perspective can be totalised and used to describe the terrain. This is a viewpoint. Particularly, it is a view up from where I stand, up through the layers of feminisms and anti-woman philosophies which loom over the sex-negative position. As a viewpoint, not a map, it makes no pretence of being complete, but I’m sharing it in case it can illuminate.

The forces:

- Sex Moralism is hegemonic, historical and contemporaneous, misogynist and anti-sexual-“liberation”. It is the controlled right of male sexual (and otherwise) access to women, in which people acting sexually outside of that controlled system are considered shameful and dirty. It is the sexualisation of feminine vulnerability but it is also coercion of women into motherhood, observance of codes of female ‘decency’ and heterosexual marriage. In the ideal state of sex moralism, all visible, primarily-white women are virgins or mothers to most men and sluts and mothers to the one man who selected them, and the prostituted class is invisible.

- Compulsory Sexuality is hegemonic, modern, capitalist, misogynist and post-sexual-“liberation”. It is the universal right of male sexual (and otherwise) access to so-called “liberated” women. Pornographic, it is full-spectrum sexualisation of all women, and of all objects and products as substitute women. It is pinkwashing and cooptive of lesbian and gay movements (and to a lesser extent, bisexual and trans* movements), as long as those movements will agree that women and female proxies must be fucked. In the ideal state of compulsory sexuality, all women are simply sluts.

Taken together, compulsory sexuality and sex moralism form a partial philosophy of women. (Not a complete philosophy: neither of these forces fully describe the situation of slaves or colonial subjects, for example.) They work together to control women, in and out of marriage, in and out of the bedroom, in and out of the brothel. The two systems are not as different as they appear, since they share a comfortable common ground: they both hate women. Even when they appear to be in conflict, you can guarantee that they will settle their differences over women’s bodies.

You could argue about which is actually more powerful; while compulsory sexuality has been in ascendence in the West since the 1960s, in many parts of the world (and indeed parts of the West) sex moralism is still a more potent force.

- Sex-Positive Feminism, as I frame it, is a marginalised, progressive force which is present-day. It is a feminist tendency which aims to fight the shaming of women and a woman’s right to independence as a sexual actor. As such, its obvious enemy is sex-moralism, which it directly opposes. And its subtle enemy is compulsory sexuality, which may easily coopt it. The job of fighting sex-moralism is straightforward if not easy. The job of resisting cooption by compulsory sexuality is extremely challenging and requires sisterhood and cooperation with sex-negative feminists. Unfortunately, many sex-positive feminists conflate sex moralism with sex-negative feminism and fight them both, leaving them wide open to being coopted into the service of compulsory sexuality.

- Sex-Negative Feminism is a marginalised, progressive force which dates from the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 60s and continues to the present day. It is a feminist tendency which speaks honestly about the hard knot of sex, power and violence formed by male supremacy and which aims to liberate women from sexual violence and compulsory sex. As such, its obvious enemy is compulsory sexuality, which it opposes openly. Sex moralism appropriates some sex-negative feminist language in its abstinence and anti-sexualisation advocacy but sex-negative feminists do not support the way it uses the language to make antifeminist arguments. Sex-negative feminism’s most complex struggle is with sex-positive feminism, which does not need to be an enemy. As sex-negative feminism does not advocate shaming or controlling women, sex-positive feminism does not need to oppose it on these grounds. But when sex-positive feminism is coopted by and advocates for compulsory sexuality, sex-negative feminism must resist, as compulsory sexuality under male supremacy is compulsory violence against women.

As I have outlined them here, neither sex-positive or sex-negative feminisms are totalising systems. Many women’s feminisms embrace elements from both categories, in that many feminists know that women must neither be shamed for sex or forced into it.

If one thing motivated me to write this article, it was this: to give a heartfelt invitation to feminists who centre a sex-positive analysis to stop fighting with and to listen to sex-negative feminist insight. Sex-negative feminists are not the political right-wing. We do not hate women. We are sisters who have a deep analysis of sex, violence, power and compulsory sexuality and have been trying to share it for over half a century. If you do not listen, your feminism risks becoming (or may have already become) rape culture in disguise.

But sometimes, there is less distance between us than we think:

We didn’t have backgrounds that one would normally consider anti-sex. We had liberal backgrounds, liberal parents, liberal educations. Why were we so attracted to the idea of taking a year without sex? I thought about it a lot, and I concluded this: We felt like we didn’t own our sexuality. We felt like our sexuality wasn’t for us. Or at least, that’s how I felt. So many things about the way I was having sex seemed to have nothing to do with me. And if sex had nothing to do with me … then why was I doing it?

When I start to think of the number of times I have been cajoled, pressured, or forced into sex that I did not want when I came into “the BDSM community”, I can’t actually count them… I realized I didn’t feel traumatized because it happened so bloody often that it was just a fact of being a submissive female.

Women as a class and as individuals, overwhelmingly, are oppressed sexually in numerous ways and that our sexual oppression is yet one more rock on the giant pile of many we’ve been stoned with that keep us down, AND hyperfocus on the sexual, or sex-as-entry to being able to bring up feminism at all is part of that… and radical feminists – those most often arbitrarily labelled as against sex and sexuality – KNOW this.

Whose are these radical, sex-negative feminist voices? They are Clarisse Thorn, Kitty Stryker and Heather Corinna (each name links to the relevant article), all three of whom are well-known writers and activists in sex-positive feminist circles.

I would like to think there is a new wave of dialogue between sex-positive and sex-negative feminists on this subject. Of the three writers quoted, Stryker is beginning to consider whether “sex is neutral” rather than ‘positive’, and while people widely call Corinna “sex-positive”, she has never described herself in that way.

In part, this article is participation in that dialogue from the ‘other’ side, and where possible I’ve favoured reaching out a hand, hoping to be met.

The Ethical Prude

Before I end this essay, I would like to touch as promised on the figure of the Ethical Prude.

If Easton and Hardy’s Ethical Slut is “a person of any gender who has the courage to lead life according to the radical proposition that sex is nice”, then the Ethical Prude lives her* life politically according to the radical feminist proposition that the thing called ‘sex’ under patriarchy is not nice. In ethics (ironically enough), we distinguish ourselves from sex moralism and in prudery, from compulsory sexuality.

(* I say “her”, as I invite men who identify with this statement to describe themselves as pro-prude, or sex-negative feminist allies, rather than taking the label for themselves. Men may support the radical feminist movement but it remains an autonomous women’s movement; sex-negativity, likewise.)

‘Prude’ is another word I would like to see reclaimed, and one I am beginning to use for myself. Reclaimed, since it is already in use, as ‘loveisinfinite’ comments on a Holly Pervocracy article about geek social fallacies of sex:

… the idea that feeling that sex actually IS a big deal makes someone a prude is far too rife in many spaces I frequent.

In our reclamatory definition, then, the Ethical Prude – from prudefemme, a wise, proud and virtuous woman – is named as such by her peers for her fearless opposition to the conflation of sex, power and violence and to compulsory sexuality. Patriarchy attempts to divide her from her friends by using her as a figure to make them feel shame, but she undermines this tactic through her fierce love for fellow women and the solidarity they have formed. Understanding sex-negativity, her friends do not allow themselves to become separated from her but recognise patriarchy in the urge they feel to turn away, and defy it.

She supports survivors who have been hurt by patriarchal sex, and other women support her, not letting any one woman buckle under the trauma of looking rape culture head-on. Spinster, feminazi, sex-negative, lesbian, witch; she is called every name but answers to only one: sister.

If you’re a fan of Terry Pratchett, you might want to consider the Ethical Prude as the Esme Weatherwax of feminism. Pratchett’s “Witches” books contain three witches: the maiden (Magrat Garlick), the mother (Gytha Ogg), and the… other one. Weatherwax is the other one. She dresses for warmth and practicality rather than to foreground sexuality. She walked away from her childhood sweetheart in order to pursue her life’s work of witchery. She’s hard-headed, has a sarcastic sense of humour and she doesn’t stand for any nonsense. (And Weatherwax as sex-negative feminist also suggests who might be a good stand-in for sex-positivity…)

I can already see the comments now – is this a demand of celibacy? Is it a return to 1981’s politically lesbian politics of the Leeds Revolutionary Feminist Group? If you’re wondering the above, first answer this: do you think that Easton and Hardy intended the Ethical Slut to be read as a demand for every woman to commit the remainder of her life to sex and only sex? (Seriously, though, Love Your Enemy is an incredible book. You should find it and read it and then share it with all your friends. Then you should become a separatist. :))

So: who is going to organise the first PrudeWalk?

Conclusion

Under patriarchy, sex is power, power is sexy, and sex is compulsory. That is to say, the sex act is attractive in a way that is conditioned by its qualities of power and violence. And that coercion is not just a property of individual sex acts, it is a property of sexuality at a social level; we are not just coerced into sex, we are coerced into sexuality, most specifically into heterosexuality, or into reproducing subject-object dynamics within our non-hetero-sexualities.

In sharing the concept for this essay with friends, one suggested that she felt we needed to overcome the binary between sex positive/negative. I hesitantly disagree. I think that binaries (and ternaries, and other models) are useful as long as we don’t mistake them for reality. Both sex-positivity and sex-negativity, if applied correctly, are useful lenses through which we can understand different aspects of patriarchy, such as sex moralism and compulsory sexuality.

It is vital that the phrase “sex-negative” stops being an insult, or at least that more feminists develop an understanding that sex is not above criticism. Not bad sex, not sex gone wrong, not the sex that other people have. Our sex, real sex, what we call sex – it must be criticised. We can find male supremacy within it and within our own heads, and if we put it beyond reproach then we are putting aspects of patriarchy beyond reproach, beyond feminist analysis. It is not; sex-negative feminists show us how.

And last: it would be traditional to end this essay with an assurance that I do, in fact, love sex, and that all I want to do is to make it better. As an Ethical Prude, I won’t write such an assurance, even though I feel under almost overwhelming pressure to do so. We’d do well to reflect on the nature of that pressure.

Lovely essay, this really captures and expands a number of topics I have been considering of late, most especially the idea of re-claiming the term prude. I would love a prude walk but fear there is a lot more discourse with sex positive feminists needed before it would be taken well.

I wanted to address one very specific point you made about asexuality and compulsory sexuality:

“As I understand it, there is an ongoing debate in asexual communities about whether compulsory sexuality and its message of “gotta fuck” is a cultural force which structurally oppresses asexual people.”

As an asexual woman, it has been my observation that this debate is a strongly gendered one. Women nearly universally perceive structural oppression, nearly every asexual woman I know has received some form of sexual harassment and violence up to and including corrective rape upon disclosing their asexuality or just a disinterest in sex. Coercion towards sexuality for women seems to come not only from the wider culture, but from within the asexual community. After a fairly brief time on the AVEN forum (so my perceptions may be biased and incomplete) I gave it up as an unsafe space after witnessing many discussions where people (but almost always women) were encouraged to “compromise” by having sex they did not want with their (almost universally male) partners, under the assumption that sex was “owed” or necessary if the woman wished to not be dumped. The discussions surrounding compromise often made the assumption that sex is consensual as long as the person ultimately says “yes” regardless of structural or interpersonal coercion, which I don’t accept, and that the primary value a woman brings to a relationship with a sexual individual is that of a sex object. I ultimately never posted because the general discourse was deeply unsettling to me.

@Framboise: I agree with you about prude walks. The idea came up at a party last year with several feminist friends, but I also felt that some more discourse would be helpful first. This article is a culmination of my thoughts on the subject and hopefully contributes to that discourse!

What you describe about asexual women’s experiences is horrible, but sadly it doesn’t surprise me in the slightest. I’m sorry that you were driven out. I had hoped to find some women’s voices on the subject of structural oppression done by compulsory sexuality towards asexual people, but I guess as usual this “driving-out” is part of the reason why those voices are difficult to locate.

To partially rectify that, do you mind if I make a hyperlink from the article body in the asexuality section, down to your comment?

Oh, not at all, feel free.

I liked this article, Lisa. (By the way, I need to add you to my link hoard :))

I think a ‘sex-positive’ and a ‘sex-negative’ feminism should be one and the same. In an ideal world(one without patriarchy) females* would be able to have sex as they wish. I do think that many apsects of the ‘sex-positive’ current in feminism is actually damaging and is often co-opted by males* seeking to force women into sex. As Framboise points out, ace females are expected to have sex where ace males ave the ability to walk out. The ace community can be really great sometimes, but as it stands it is infected with patraiarchy too. (As you know, I am a demisexual and share some of the same issues as an ace might).

What I think is symptomatic of patriarchy is this assumption that just because I don’t think things like BDSM or poly are inherently wrong(ironically I’m kinky and poly) and that it’s right for some people does not mean I think every single person must engage in kink or poly. Not to mention in some religious(usually pagan) communities there are serious issues regarding what sexual roles people in general must have.

Awesome essay with loads to chew on, thanks!

Have you read Pornography and the doubleness of sex for women, by Joanna Russ? [TW for discussion of rape and sexual coercion.] I thought of it a couple of times when reading this.

@Lilka: Thank you! That was an amazing read! And again, from twenty years ago. How disappointing; that material two decades years old can still be a revelation and has not become part of our feminist fundamentals. There’s so much to do. But thank you for unearthing this for me.

I really like your identification of compulsory sexuality. Many people feel that they need to signal “I like sex and want to have it” as an “admission ticket” to discussions about sexuality and gender relations.

Do you think there’s a difference between an individual’s sex-negative feminism that comes from being asexual or having a low sex drive, and hence not wanting sex of any kind right now, and sex-negative feminism that comes from the recognition that sex in this society can’t be divorced from the horrible attitudes to it?

One thing I’m not sure about is that you describe sex-negative feminism as an autonomous women’s movement, and ask men to identify as allies instead – but where does that leave people who identify as neither male nor female?

@David: I think that political sex-negativity and asexuality are very different, yes. I don’t really see how they’re similar.

As mentioned in one of the introductions, where I use ‘woman’ on this blog I’m usually referring to people treated politically as women, that is, people who are identified by patriarchy as and oppressed as women, and who also identify their class interests as being women’s class interests.

Oops, I haven’t checked blogs in a couple of days and thus I almost missed this gem. I’ll admit, as a FAAB person of marginalized gender/sexual identity who has an extraordinary libido and a strong preference for radical(ized) kink, I wasn’t sure what to expect going into this— though I also have pretty much always had objections to the common formulations of sex-positive feminism that have been co-opted by the patriarchy for bizarre arguments like “watching Sex in the City is an inherently feminist act” or “choosing to wear makeup is an inherently feminist act.” On the one hand, sex isn’t just nice for me, it’s absolutely awesome, and within a monogamous context I’ve grown very adventurous with it over the past couple years; on the other hand, I have still experienced very not-nice sex, which I will not call rape but which went together with actual sexual abuse and rape-narrowly-avoided. I don’t know how any sex act, any sexualized act, or any gendered act can be inherently feminist at all, whether that means being as “slutty” as possible or as “prudish” as possible. And yet! Your post here has synthesized and harmonized my own divided views into something that, in my opinion, really works quite well. The crucial part is toward the end where you suggest the battle that sex positivity primarily wages against sex moralism as only SECONDARILY against compulsory sexuality (while being at risk of co-optation in that case), while on the flip side sex negativity primarily battles compulsory sexuality and only secondarily sex moralism. I think you’ve fantastically summed up how these two “different” feminisms don’t actually have to be at odds, they’re just focused on distinct issues within the broader spectrum of patriarchy.

I think this article is really, really excellent, and I definitely agree with your analysis.

I have one thought to offer about where it might go from here. Thinking about the prospect for some sort of synthesis (or accommodation, or alliance, or something?) between sex-positive feminism and sex-negative feminism, I am reminded of Nancy Fraser’s article ‘From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a Post-Socialist Age’ (link: http://www.newleftreview.org/?view=1810). Briefly, Fraser argues that oppressed groups experience two different types of injustice: socioeconomic injustice and cultural/symbolic injustice. These two kinds of injustice have different remedies. Socioeconomic injustice requires redistribution, which involves countering the idea that the oppressed group is any different from anyone else. Cultural/symbolic injustice requires recognition, which involves affirming the distinctive identity of the oppressed group, resisting its degradation, marginalization or erasure. These two remedies, then, pull in different directions, but many groups (e.g. women!) experience both types of oppression. Fraser then goes on to offer a suggestion as to how this ‘redistribution-recognition dilemma’ could be resolved, which she describes as ‘transformative’. Basically, the idea is to disrupt the dilemma by challenging the underlying social structure that generates the injustice in the first place (e.g. through socialism and the deconstruction of the gender binary).

This is a very sketchy summary, but basically my thought is that this might be relevant to your discussion because the recognition-redistribution dilemma might map onto the 4-way map you gave of sex moralism, compulsory sexuality, sex-positive feminism, and sex-negative feminism (sex moralism and compulsory sexuality as the two injustices, sex-positive feminism and sex-negative feminism as the two remedies). So the idea would be that women are subject to two different injustices in the form of sex moralism and compulsory sexuality, and they have to find a way to resolve the apparent tension between the two different remedies to those injustices (sex-positive feminism and sex-negative feminism). For what it’s worth, I think Fraser’s solution to the redistribution-recognition dilemma is rather good, and I think if it was applied here it might nudge us towards a ‘sex-critical’ feminism that emphasizes the ‘transformation’ of current structures of gender.

Hmm. I’m not sure if that really makes sense, but anyway, it was a thought I had. Thanks very much for the article!

@feministphilosopher: In general I like the ‘transform the territory’ approach to the whole ‘normalising vs. identity activism’ problem.

I think that, in feminist terms, ‘transform the territory’ often just means doing radical feminism. 🙂 Radical feminism’s the only feminism I know which is advocating the complete uprooting of gender.

Specifically in the realm of sex, though, I don’t know. Destroying gender would probably do it, but I think there are other transformations to look at as well. Not instead of destroying gender, but possibly until we destroy it, and even maybe doing them may give us some clues / tactics for destroying gender.

Something I’m planning to do in my next article is to try to sketch out what some transformative alternatives to sex (if, for the sake of this sentence, I cede that word entirely to the patriarchy) might be…

I’m a sex-positive feminist; I see sex-positive feminism as the place where people are trying to create better sexualities, imperfect though they might be. I came here via my sister’s facebook. After reading this, I’d go on a PrudeWalk. I’m glad to add this lens to my ways of looking.

This is amazing. I feel utterly ridiculous for never having considered that an alternative to sex-positivity might not necessarily be a bad thing. Thanks for supplying much food for thought, and for setting out your framework so clearly at the beginning of your essay – as an academic I appreciated that very much!

Lisa – Yes! As ever, Doing More Radical Feminism is most definitely The Solution. Love it.

I think we would need to transform both gender and also sexuality, which of course are two aspects of the same power dynamic (love MacKinnon’s moving/congealed thing on this) but this process might look different depending on which aspect, gender or sexuality, we foregrounded when we analysed it.

I think the way you configure sex-negative feminism is such a profitable line of thinking. Looking forward to the next article.

Pingback: Sex-negative spaces « Pyromaniac Harlot's Blog

This is fantastic. I am a law student and just shared this with my feminist criminal law professor, who relies extensively on MacKinnon in her critiques of rape law. I am interested to see if she will read it and comment.

As someone who identifies with “slut” in the polyamorous sense, and found The Ethical Slut to be very liberating and affirming, I appreciate this essay *just as much* as I did that book. Particularly, I find the insistence that we recognize that the nice, feminist sex that some of us may be enjoying is NOT the reality for the majority of female bodied people, or anyone, for that matter.

Thank you for this refreshing reminded that all decisions re: sexuality are, when arrived at through one’s own free will and reflection, just as respectable as any other.

Pingback: Asexuality | Pearltrees

Wow, so much food for thought! So many books to check out! As usual, I’ve gotta read three of four or ten more books before I have something to contribute really. But in brief, I am one of those sex-positive feminists who has mistakenly believed myself at odds with sex negative feminists in the not so distant past. Yet I’ve also considered the implications of compulsory sexuality coopting sex positivity, and I’ve also been accused of *being* sex-negative when I approach intersections of sex, desire, power, violence, and control with a critical eye. I’m behind on my theoretical reading, but light years ahead on the fiction front. From that standpoint I’d rec Luisa Valenzuela, and most especially the collection ‘Cambio de Armas’ trans as ‘Other Weapons’ and Diamela Eltit + Paz Errazuriz ‘El Infart Del Alma’ recent trans is decent, tho unfortunately titled ‘Soul’s Infarct’. Thanks for the awesome breakdown!

This is the best article I have read in such a long time.

Kudos to you.

@ David: I have a very strong libido, but I also count myself as sex-negative. I like my head to rule my body, and I rather think critically about what society needs compared to what society tells us *we* need.

Plus, it means I get to be a threat to civilisation itself. How flattering!

Wow, finally got around to reading this and really enjoyed it. It gave me comfort as it cements a lot of what I have felt intuitively and felt uncomfortable with, because it conflicted so much with what many people around me were saying.

Pingback: Towards a sex-neutral feminism – Second Council House of Virgo

Pingback: Sex-Positive Feminism vs. Sex-Negative Feminism « Shades of Gray

I’m quite a new feminist who would ordinarily indentify as sex positive and as such reading this has left me with mountains of questions.

I don’t know if you’re still responding to this so I’ll keep it brief: how would this translate into action/behaviour? The ethical slut obviously feels no guilt/remorse for any sexual exploits that she undertakes of her own choosing and I think it would be wrong to say that sex negative feminist would be the direct opposite of this and both avoid and heavily criticise herself and others for their sexual behaviour? I get that sex in itself in this view is seen as an agent of the patriarchy (to use a horribly overarching term) but I’m confused how this translates into the day to day.

Thanks and it was a really interesting article!

@olli: Don’t think of sex-positivism and sex-negativism/radical feminism as opposites. When sex-positive feminism’s functioning correctly (and it’s often a problem that it’s not, and that it’s pushing compulsory sexuality on the side, but that’s a side note) then it’s doing its work taking down sex moralism, like you describe. Sex-negative feminism, on the other hand, is about tackling compulsory sexuality. So that means always bringing in the critique of social patterns, never letting the statement, “Well, I didn’t feel very coerced that one time, so thus there is never any coercion for anyone!” creep in to her politics, asserting the political in the personal at every step.

So how do these politics translate into the day to day? They translate by understanding what sex means under patriarchy and then attacking that. Some day to day things you could do would be to support survivors, e.g. learn more about abuse so that you can help people who’ve experienced abuse, or if you’re a survivor yourself work on your own healing, you could write articles like this one, you could – well, there are all kinds of feminism to do!

The majority of them don’t mean having sex. I don’t think that having sex is necessarily a fundamentally revolutionary activity. It’s actually very difficult to have good sex when you really look unflinchingly at what sex means in this society. But it is possible. The next thing I’m planning to write here will be more about that, so stay tuned if you’re interested. 🙂

Oooh, this is a very interesting post. I haven’t had time to digest it thoroughly and am not sure I agree with all of it, but some bits had me jumping up and down and I think it may have spurred an epiphany on what connects various issues I’ve been harping on about forever.

I do want to make a point on the asexuality thing: “As a relatively new movement, it may be that there has not yet been time for a sufficient diversity of asexual activists to find their voices, or it may be that there are simply no systems in which asexuals are oppressed qua (as) asexuals.”

I think the issue is that we’re out there but pretty much invisible? Like, very roughly speaking I would split up the asexual/asexual spectrum community into the bits that are mostly concerned with increasing visibility, the bits mainly concerned with building community and the ones that are mostly concerned with activism (in the “talking about oppression” sense). With obvious overlap. AVENues, which you quote, and AVEN, which Framboise quotes, I’d stick more into the first category – and there are some very problematic attitudes at play there (I am at both appalled and sadly unsurprised at Framboise’s experience of the AVEN forums…), and I and other people who are more of a social justice bent have been pretty frustrated by the “but we have no problems really!” attitude that often gets promoted, among others.

On the activist side of things, there’s an ace blogosphere and some other places online – the asexual tag on tumblr often gets this sort of discussion when it’s not utterly besieged by people who hate us. The main issues seem to be that people outside our communities don’t realise we exist, and that when they do we get hit with a lot of backlash and hatred. I’ve seen people trying to address the question of “are asexuals oppressed qua asexuals” and then *sexual people jumping in furious with rage at the idea that we claimed to have any problems at all let alone be marginalised compared to them. (There was an attempt at a *sexual privilege checklist on tumblr about ten months ago. It didn’t end well.) I wouldn’t be surprised if I wasn’t the only ace on the more activist side of things who now tries to dodge that question entirely and instead tries to describe ace oppression as a specific presentation of heteronormativity.

Er and that had next to nothing to do with your post! I just got a bit grumpy at what I saw as a misrepresentation of my community.

On topic – your idea about tearing down this dichotomy we’ve built up between “sex” and “rape” set off fireworks in my head. Because, mm, there are a few things I keep harping on about regarding ace issues and this ties them together. Things like how compulsory sexuality leads to a lot of ace people being pushed into having sexual encounters they may find uncomfortable/unpleasant all the way to traumatising, but in ways that don’t necessarily fit well into the usual rape/sexual assault narratives. (And that doesn’t have to mean pushed by specific people.) Or how the model of enthusiastic consent that I frequently see pushed as the end-all be-all of consent models doesn’t really work very well for a lot of ace people. (Some readings leave us unable to consent to sex at all. This is not helpful and kind of insulting.) Or, generally, how a lot of the dialogues I’ve seen about sex and sexuality assume “sex is inherently a good thing” in ways that are both alienating and mean they can’t actually address many ace issues – because for many asexuals all sexual encounters have a negative component and that has to be addressed without demanding all of us be celibate forever. I think this even ties in with the demonisation of asexual people in sexual relationships you see a lot, huh.

Hey, Kaz. Thanks for the comment!